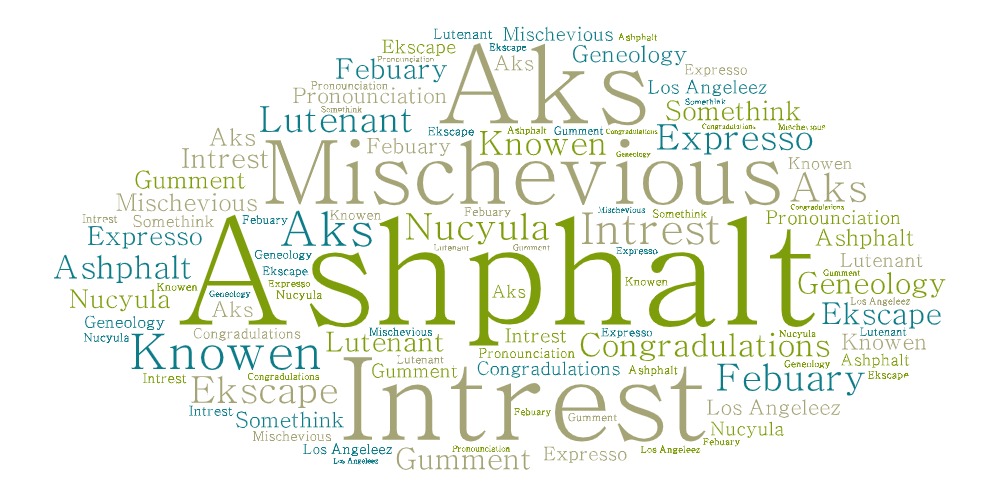

Word cloud made with wordart.com

This is what I wish everyone could think when they hear someone else speak in a different language, accent, or dialect: “The words you speak are beautiful.”

But often the response is expressed as amusement, superiority, or outrage. On Thursday last week, the ‘Question of the day’ on Radio New Zealand’s afternoon show The Panel was, ‘What is the mispronunciation that really grinds your gears?’

It was clear from the host Wallace Chapman that he knew he would get a high level of reaction, and sure enough the response was reportedly huge. Listeners wrote in with examples of ‘incorrect’ words used in NZ English, often reflecting what I would describe as normal rapid speech (see word cloud).

I turned the radio off. But I was curious – I turned it back on again. And then I texted in:

Come on Wallace

Are we really still doing this? Can’t we enjoy watching our language in all its variety?

Hilary (sociolinguist and proud Kiwi English speaker)

My text was ignored, as I suspected it might be, because my approach was not buying into the ‘correct/incorrect’ discussion. Although there was disagreement about some of the words by the panellists, the idea itself was unchallenged. It seemed to be light-hearted, but was it really?

NZ English was part of the ‘colonial cringe’ for many years when British English was the standard to be aspired to. But now it is regarded proudly as a reflection of our identity and the discussions on The Panel did not seem to be worried about Kiwi English per se.

There was mention of language change. That has been a discussion in English since Geoffrey Chaucer wrote some time in the 1380s:

Ye knowe eek, that in forme of speche is change eek - also

With-inne a thousand yeer, and wordes tho

That hadden prys, now wonder nyce and straunge prys – value, price

Us thinketh hem; and yet they spake hem so, nyce - foolish, uncultivated

And spedde as wel in love as men now do; spedde - succeeded

Eek for to winne love in sondry ages, sundry - different, sundry

In sondry londes, sondry ben usages. ben - exist

Troilus and Criseyde Book 2, lines 22-28

Translations from: Middle English Dictionary

We all know English has changed over the hundreds of years it has been spoken, but there still seems to be the thought that somehow language should not be changing in our lifetime.

Resistance to language change is possibly the result of prescriptive the approaches which have influenced the teaching of English since the 18th century, and which drive the ‘language police’ and the prejudices they show. Prejudice leads to inequality, and plenty of studies show that ideas of language ‘correctness’ help to maintain hierarchies of inequality, which is the pernicious aspect of the RNZ discussion.

However, later in the conversation Wallace Chapman said that it is not really about language, but about changes in society. “People have had enough”, he said.

So, if we are worried about the changes in society, I wish we could encourage people to use our democratic processes to improve things. And when we hear someone speaking differently from ourselves, I wish we could train ourselves to think, “The words you speak are beautiful.”

PS Chaucer wrote ‘ax’ for ‘ask’.

Hi Hiraly,

Thanks for the link to your article.

I just wanted to say that I think this is a really important subject for a whole host of reasons – all of which you talked about very eloquently.

I also think we have to accept that young people, often criticised for being on their phones all the time, are not reading less those in the past. In fact, they’re probably reading more. The area of difficulty we have to address, however, is that they might need exposure to a broader sense of audience (and language), so that they can participate more fully.

I know this is not precisely the area you discussed, but it’s a particular bug bear of mine that I think is really important. Sadly, it gets a ho hum from people when I bring it up. so… I took this opportunity to bang on a little about it.

Take care, and we’ll talk soon.

Marg

LikeLike